وجد الباحثون أن الكائنات الحية طويلة العمر غالبًا ما تُظهر تعبيرًا عاليًا عن الجينات المشاركة في إصلاح الحمض النووي ونقل الحمض النووي الريبي وتنظيم الهيكل العظمي الخلوي والتعبير المنخفض للجينات المسؤولة عن الالتهاب واستهلاك الطاقة.

يقترح الباحثون في جامعة روتشستر المهتمون بعلم وراثة طول العمر أهدافًا جديدة لمكافحة الشيخوخة والاضطرابات المرتبطة بالعمر.

تم تكوين الثدييات التي تقدم في العمر بمعدلات مختلفة جدًا عن طريق الانتقاء الطبيعي. على سبيل المثال ، يمكن أن تعيش فئران الخلد العارية حتى 41 عامًا ، أي 10 مرات أطول من الفئران والقوارض الأخرى ذات الحجم المماثل.

ما الذي يسبب إطالة العمر؟ قطعة مهمة من اللغز ، وفقًا لدراسة حديثة أجراها علماء الأحياء من جامعة روتشستر ، يوجد في الآليات التي تتحكم في التعبير الجيني.

فيرا جوربونوفا ، أستاذة علم الأحياء والطب ، دوريس جونز شيري ، وأندريه سيلوانوف ، المؤلف الأول للنشر ، جينلونج لو ، باحثة ما بعد الدكتوراه في مختبر جوربونوفا ، وباحثون آخرون نظروا في الجينات المرتبطة بطول العمر في مقال نُشر مؤخرًا في المجلة. الأيض الخلوي.

أشارت النتائج التي توصلوا إليها إلى وجود آليتين تنظيميتين تحكمان التعبير الجيني ، والمعروفين باسم الشبكات البيولوجية وتعدد القدرات ، وهما أمران حاسمان لطول العمر. النتائج مهمة لفهم طول العمر وكذلك توفير أهداف جديدة لمكافحة الشيخوخة والاضطرابات المرتبطة بالعمر.

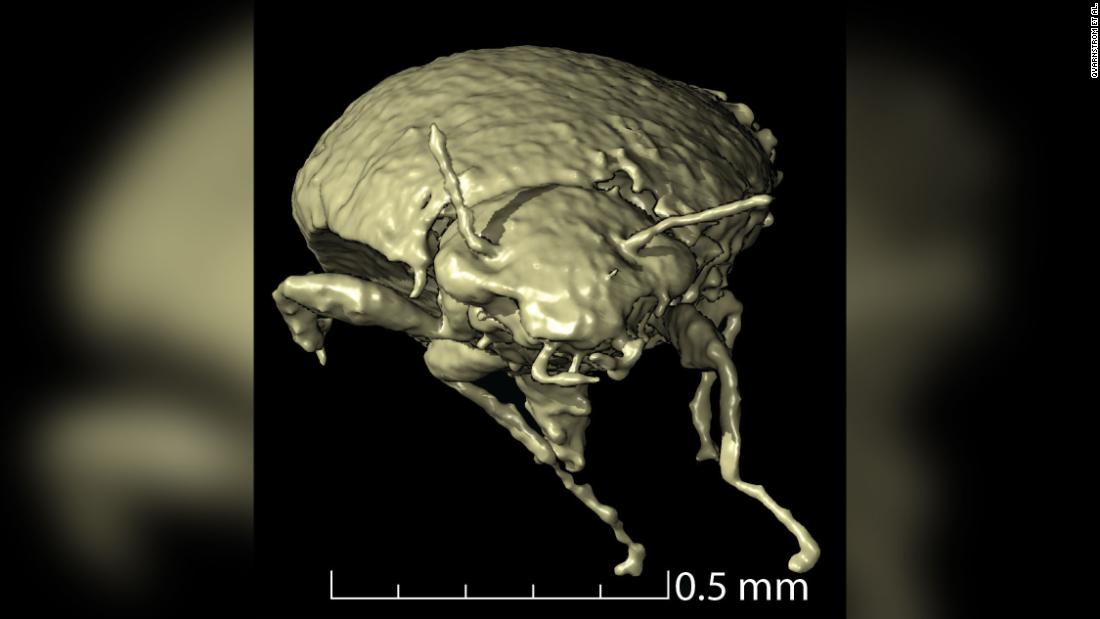

من خلال مقارنة أنماط التعبير الجيني لـ 26 نوعًا بأعمار متفاوتة ، وجد علماء الأحياء بجامعة روتشستر أن خصائص الجينات المختلفة كانت تتحكم فيها شبكات الساعة البيولوجية أو شبكات تعدد القدرات. الائتمان: جامعة روتشستر التوضيح / جوليا جوشبي

قارن بين جينات طول العمر

بأعمار قصوى تتراوح من عامين (الزبابة) إلى 41 عامًا (فئران الخلد العارية) ، حلل الباحثون أنماط التعبير الجيني لـ 26 نوعًا من الثدييات. اكتشفوا الآلاف من الجينات التي ترتبط إيجابًا أو سلبًا بطول العمر ومرتبطة بالعمر الأقصى للأنواع.

ووجدوا أن الأنواع طويلة العمر تميل إلى التعبير المنخفض عن الجينات المشاركة في استقلاب الطاقة والالتهابات. والتعبير العالي للجينات المشاركة في[{” attribute=””>DNA repair, RNA transport, and organization of cellular skeleton (or microtubules). Previous research by Gorbunova and Seluanov has shown that features such as more efficient DNA repair and a weaker inflammatory response are characteristic of mammals with long lifespans.

The opposite was true for short-lived species, which tended to have high expression of genes involved in energy metabolism and inflammation and low expression of genes involved in DNA repair, RNA transport, and microtubule organization.

Two pillars of longevity

When the researchers analyzed the mechanisms that regulate the expression of these genes, they found two major systems at play. The negative lifespan genes—those involved in energy metabolism and inflammation—are controlled by circadian networks. That is, their expression is limited to a particular time of day, which may help limit the overall expression of the genes in long-lived species.

This means we can exercise at least some control over the negative lifespan genes.

“To live longer, we have to maintain healthy sleep schedules and avoid exposure to light at night as it may increase the expression of the negative lifespan genes,” Gorbunova says.

On the other hand, positive lifespan genes—those involved in DNA repair, RNA transport, and microtubules—are controlled by what is called the pluripotency network. The pluripotency network is involved in reprogramming somatic cells—any cells that are not reproductive cells—into embryonic cells, which can more readily rejuvenate and regenerate, by repackaging DNA that becomes disorganized as we age.

“We discovered that evolution has activated the pluripotency network to achieve a longer lifespan,” Gorbunova says.

The pluripotency network and its relationship to positive lifespan genes is, therefore “an important finding for understanding how longevity evolves,” Seluanov says. “Furthermore, it can pave the way for new antiaging interventions that activate the key positive lifespan genes. We would expect that successful antiaging interventions would include increasing the expression of the positive lifespan genes and decreasing the expression of negative lifespan genes.”

Reference: “Comparative transcriptomics reveals circadian and pluripotency networks as two pillars of longevity regulation” by J. Yuyang Lu, Matthew Simon, Yang Zhao, Julia Ablaeva, Nancy Corson, Yongwook Choi, KayLene Y.H. Yamada, Nicholas J. Schork, Wendy R. Hood, Geoffrey E. Hill, Richard A. Miller, Andrei Seluanov and Vera Gorbunova, 16 May 2022, Cell Metabolism.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.04.011

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging.

“هواة الإنترنت المتواضعين بشكل يثير الغضب. مثيري الشغب فخور. عاشق الويب. رجل أعمال. محامي الموسيقى الحائز على جوائز.”